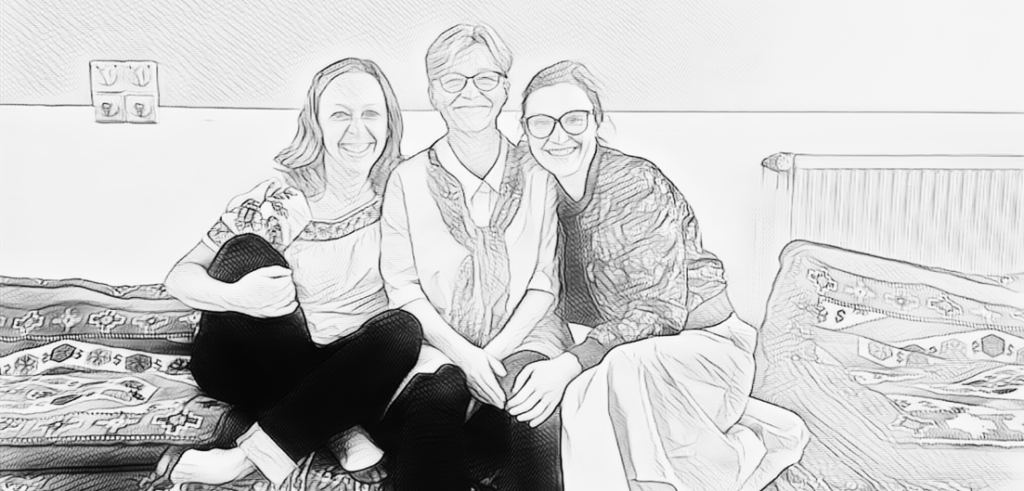

Mnemo ZIN is a composite name for Zsuzsa Millei, Tampere University, Finland; Iveta Silova, Arizona State University, USA; and Nelli Piattoeva,Tampere University, Finland. Our collective name is inspired by the stories from the Greek mythology, especially the figure of Mnemosyne, the goddess of memory and the mother of the nine Muses. Mnemosyne was the daughter of Gaia. The name is derived from the Greek word mnēmē, which means “remembrance, memory.”

Zsuzsa Millei, Professor of Early Childhood Education, Faculty of Education and Culture, Tampere University, Finland

I was born and earned my Masters degree in Hungary. After migrating to Australia in 2000, I enrolled in a PhD program. My PhD thesis focused on the history of early childhood education and care in Western Australia and the ways in which children were governed as liberal citizens through their care and education. I had to be persuaded that there might be value in comparing the historical and present Australian system to the socialist Hungarian one, which I undertook later as part of a project in 2010-2014. I am still somewhat puzzled when researchers express enthusiasm for my research on the socialist Hungarian kindergarten. Perhaps it is due to my upbringing in a socialist country characterised with explicit official politics. At the same time, perhaps growing up in this context is what fuelled my interest in researching children as political subjects and their participation in politics, the politics and biopolitics of childhood, and early childhood education and the preschool as a political and intergenerational space. Currently, I explore everyday nationalism in children’s preschool lives, and (post)socialist childhoods and schooling through auto-ethnography and collective biography and from a de-colonial perspective. This project is part of this current interest, and is located at the interdisciplinary fields of early care and education, childhood studies, children’s geographies, socialism and nationalism.

Nelli Piattoeva, Associate Professor, New Social Research Institute and Faculty of Education and Culture, Tampere University, Finland

I was born and raised in the Westernmost part of the USSR and continued my education across the border in Finland where I currently live and hold an academic tenure. I come from an ethnically mixed family and I have always experienced my identity as multi-layered, unstable, and vulnerable due to frequent questioning by the outsiders. Despite my multicultural background and the fact that I have lived in Finland for most of my life, I am perceived as uniculturally Russian, while in Russia, where I do most of my fieldwork, my living abroad and affiliation with a “Western” university may cause uncertainty and discomfort as people are unable to position me clearly as either Russian or foreign. It is perhaps due to this feeling of “out-of-placeness” that I became interested in the questions of citizenship and national identity, and their changes in the aftermath of the disintegration of the USSR.

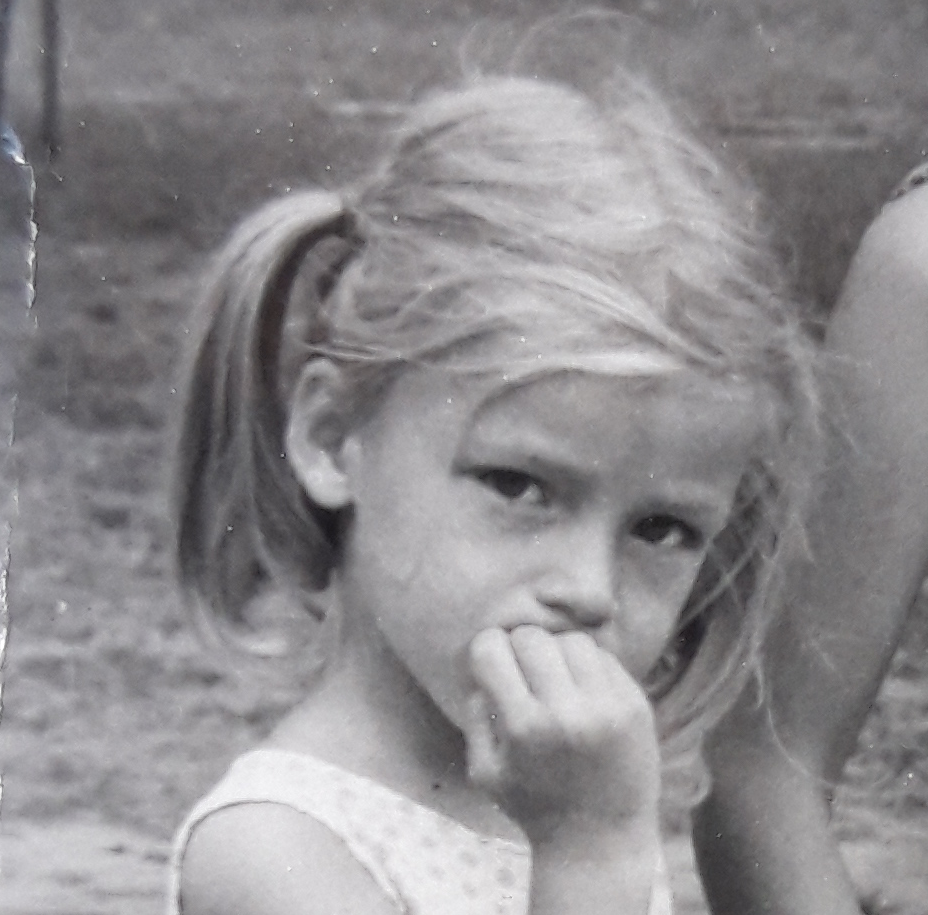

As a child growing up during perestroika, I remember personally how the opening up of the Soviet society – particularly the removal of taboos on the discussion of the crimes committed by the Communist Party – caused collision among students and school teachers. That is perhaps when my overall interest in the relationship between schooling and society was seeded. I remember my childhood as happy and carefree (even though I had to accompany my Babushka in long cues for dairy and meat products!). I remain puzzled about the intellectual wealth of my proximate environment. I grew up with incredible books, frequent visits to theatres and concerts; I overheard my parents’ political discussions and observed them developing the most incredible ties of friendship devoid of any hint of ideological content. It is the complexity of these personal experiences, mine and others’, that I want to shed light on by working on this project. Moreover, I am interested in the question of how understanding (post)socialism could help us understand life under neoliberalism, and how theoretical insights developed in the context of socialist societies could be helpful in understanding contemporary developments. My other research interests are focused on the transnationalization and datafication of education policy, and I am interested in national and international large-scale assessments as sources of evidence for policy-making and new technologies of governance at a distance. In the context of post-socialist transformations, I also examine Russia as a re-emerging aid donor, ongoing changes in the aid donor architecture and the role of international organizations in these processes.

Iveta Silova is Professor and Director of the Center for Advanced Studies in Global Education at Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College, Arizona State University, Tempe, USA

When the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, I was a high school student in Stuchka, a small Soviet town in the middile of Latvia named after Lenin’s colleague Petr Stuchka, who founded the Marxist Party in Latvia, served as the head of the Bolshevik government during Latvian War of Independence, acted as editor of major Latvian and Russian communist newspapers, and was the first president of the Supreme Court of the Soviet Union, among many other duties. His statue, once proudly towering near the House of Culture in my hometown, was hurriedly removed and the town renamed Aizkraukle,the historical local name of the hill used by the German knights in the Middle Ages. The changes that followed put everything in flux. I especially remember the year when our high school leaving examination in history was cancelled, because everyone then officially knew that the history we learned was wrong but the new history was et to be written. This moment of “in-betweenness” was both intimidating and exhilarating, and it was ultimately the moment that set the course for my academic and professional career. Straddling both Soviet and post-Soviet experiences, I became fascinated with observing, understanding, and reflecting on post-socialist transformations and their impact on our past, present, and future.

Growing up in Soviet Latvia, I was a part of an ethnically diverse and bilingual family. I quickly learned to function in the “border zone” of different political, linguistic, and ethnic identities, easily moving in and out of spaces depending on particular circumstances and contexts. My identity became more complicated when I moved to the US to complete master’s and PhD degrees and then moved again to Central Asia and the Caucasus to begin my academic and professional career there. I found myself in a much broader “border zone,” which now expanded to include global, national, and subnational identities. In Central Asia, I was perceived as “one of ours” by my local colleagues because of our shared Soviet history and, at the same time, as a legitimate member of the international development community by “Western” colleagues because of my degree from an American university. As I moved “West” to become a university professor in the United States, my previous academic and professional experiences were quickly discounted as not “Western enough” so my tenure clock had to start from zero and my academic identity had to be rebuilt from scratch. Shifting between these different roles has been both fascinating and complicated. I always felt fortunate to be a part of the different “worlds” even though I knew that I never fully belonged to any of them. I always have been and continue to be at the “borders.”