The year is 1982. It’s summer. She’s six years old. She comes from a little town in the East German countryside. She has a hunch that there’s an entire world out there, but that’s a very abstract thought for a little girl. The sleepy small town is real, a little oasis where peace and quiet couldn’t possibly be disturbed.

But it’s nice to think that there’s an entire world out there to be explored, and she’s ready to go. On this particular summer weekend her parents decide to go all the way up to East Berlin to visit Dad’s boyhood friend Martin. He and his boisterous wife Rosi are dear friends, but the girl remembers only this one visit. She doesn’t know why there’s only one memory of a visit to them in East Berlin. Or was there something so special about this trip that it stuck?

She doesn’t remember how they get to Berlin, so this part of the trip is not important. It takes three hours, and they probably drove, because Dad always drives. He only takes trains to work, but with the family—never. It’s Dad and the Wartburg. That’s how the family moves about.

At that time, Martin and Rosi live in central Berlin, a little street very close to Alexanderplatz. It’s only a five-minute walk or so to the TV tower. Of course, they start out their Berlin-adventure by sightseeing. There’s a picture of the girl and her older brother standing in front of the TV-tower. Dad took that picture. He’s the only one who can handle the camera. But his pictures tend to be terrible. He fumbles so long with the settings that everyone tends to have lost interest by the time he finally shoots the picture. He’s never going to win any prizes for those, and the family will have to put up with snapshots of themselves turning away from interesting sights. The problem won’t go away until Mom finally takes over the family-picture-taking with the advent of digital photography. But that’s not going to happen for another twenty years.

Meanwhile, the family moves on along Unter den Linden back in the summer of 1982. They pass by the tomb of the Unknown Soldier, where some East German military men stand motionlessly to honor the dead. It’s not quite clear to the little girl why standing still honors anything, but she senses somberness and for once she doesn’t feel an urge to move about but rather to cling to her Mom’s hand. The family waits to see the changing of the guard. The little girl finds it intimidating above all. The soldiers stare past the crowds and move in squares—she doesn’t know how else to describe it. No person she knows would ever walk that way.

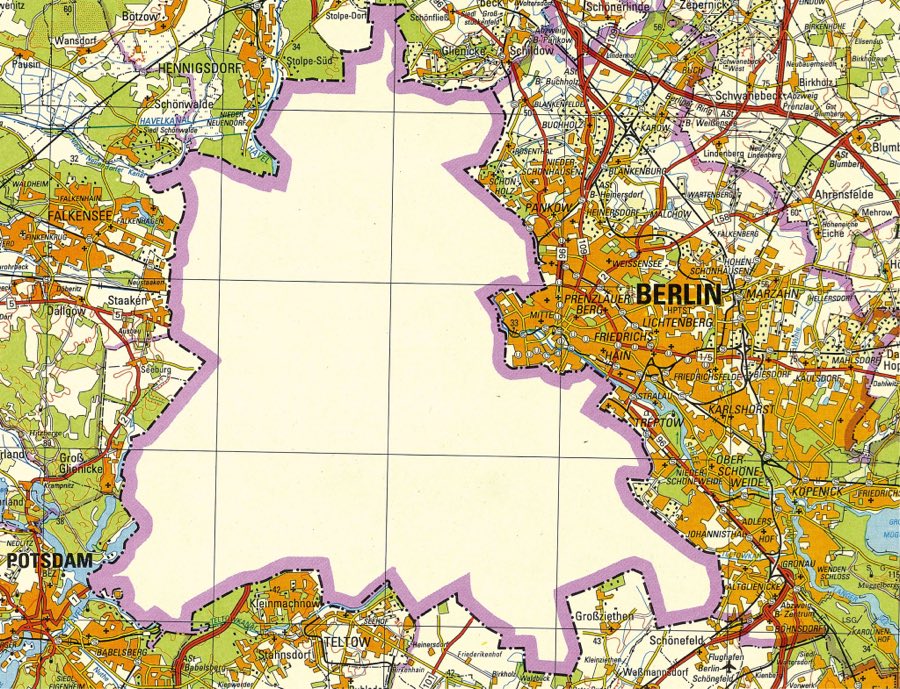

The family moves on. There’s another picture taken with some huge gate in the back. The girl feels a bit uncanny thinking of that gate. It’s an impressive gate, but there’s a rather ugly wall running right through it. No one goes near it, no one could possibly pass through it, and there are soldiers yet again. She doesn’t remember if anyone explains to her what that gate is, and why they built that wall to close it up. She doesn’t remember if she knows—or senses—what is beyond that gate. If there’s anything beyond it at all. Maybe it’s simply the end of the world? But her sense intensifies of something else being out there somehow. Her parents say that beyond the gate is the other half of the city, the Western half, and it’s supposed to be an entire city on its own. In short: it’s one of those confusing adult-things. Her mind wanders off.

It’s getting late and they’re turning back. They’ll stay with Martin and Rosi that night. The little girl very well remembers entering their house and once again finding comfort in clinging to Mom’s hand. It’s a scary staircase. It’s dark and dirty. You couldn’t possibly tell if the walls ever saw any paint, and, if so, what color it might have been. Remembering this staircase later in life, she always has a sense of “pimps and whores” frequenting that place, but the little six-year-old girl couldn’t possibly have known about sex workers. Her parents must have told her much later that the house was in a drug district. Drugs in the GDR?!? How did that come about?

She doesn’t know. Neither does she know why friendly Martin and lovely Rosi live in such a house, on such a street. They clearly were never part of that staircase-world. That’s simply where they were “lucky” enough to get an apartment assigned. And the little girl learns that the staircase and street are meaningless. For as they ring the bell and Rosi opens the door and closes it behind them—they enter a totally different universe. The girl remembers a very clean and very bright white Mohair rug right there on the floor. She remembers a stylish and elegant flat as she has never seen before. She remembers feeling happy and cosy inside that apartment. It’s with relief that she allows her Mom and Dad to make up a bed for her in one of the rooms of that very nice apartment.

As she’s lying in bed that night, the moon lightens the room through the window, she can hear a sort of rumble coming from below. She doesn’t know what that rumble is. Is she scared? No, just wondering. Once again she has this strong sensation of another world being out there. She must have gotten up to ask her parents about it, maybe even asked her older brother, who’s already in school and knows so much more than she does. What is this rumble? It’s a short rumble, then it stops, and after a while there’s another one. What is it?

The adults are having a glass of wine in the living room. They tell her that it’s the rumble of an underground train running right underneath the house. How fascinating! She’s never been on an underground train. Can we go? Maybe tomorrow, before heading back home, she asks.

They cannot go. They cannot take that train. Why not? Why not ride underneath the house where they are staying tonight? It would be so much fun to think of the house above, the cosy apartment, their joyful friends while passing by underneath. It doesn’t make any sense not to go.

The girl’s father has this peculiar smile. It’s a smile of knowing and caring, a bit mischievous as well while reflecting the absurdity of life and concluding how the only thing one could do about it is smile. He says that the train she hears doesn’t exist.

Bummer. How can the train not exist, the girl wonders. She heard it. She even felt it.

They explain that it’s a ghost train.

Oh no! Spooky! A ghost train! Does it have real ghosts on board? Would they come up to the apartment? She’d rather not have ghosts in the house.

No, they explain to her, no ghosts. It’s a train passing from West Berlin to West Berlin underneath a little stretch of East Berlin. It’s not about white bed-sheet-ghosts. It’s a train that never stops in East Berlin, so they won’t ever be able to get onto that train. That’s why they call it a ghost train. They can hear it, they can feel it, but it’s not a part of their world, which is why it doesn’t exist.

Bummer again. That’s a lot to digest. The little girl spends the night in an improvised bed in a strange house in an odd city (or two odd cities??), listening to trains that aren’t really there. Yes, truly, there’s gotta be a whole different world out there, and she has only a slight clue about it. It’s quite a bit to swallow, for a six-year old. But it’s also kind of curious and even comforting. It’s a pleasant rumble, and the girl’s quite content as she’s slowly dozing off.

Postscript

The year is 2018. The little girl has grown to be a woman, and she has a little girl now herself. It’s summer, and this new little girl is one month shy of her 6th birthday. The family decides to go on a trip to Berlin, all five of them, Mom, Dad, the girl and her two younger brothers. They’re taking the stroll from Alexanderplatz along Unter den Linden to Brandenburg Gate. It’s goose-bumps-time for the woman and her husband. She has the images of 1982 in her head. Black and white.

In 2018 everything’s in color. The place is crowded with tourists. They’re taking a family picture in front of the Gate with all those people all around them. The only soldiers to be seen now are small business people donning Cold War uniforms trying to sell souvenirs.

The woman tells her daughter, “Berlin used to be two cities, and this is where the border was, running right through this Gate. Now it’s one city again. It’s good!” The little girl listens politely. The woman can tell that her mind is elsewhere. She can tell that her little girl has no idea what she’s talking about. This bustling city being two? The idea is way too abstract. It’s absurd.