In our research project, ‘Re-Connect / Re-Collect: Crossing the Divides through Memories of Cold War Childhoods’, we explore memory stories created in collective biography workshops that tell about experiences of childhood in socialist societies during the Cold War. The project brings into view personal histories with an aim to connect generations and the public across still existing divides. Utilizing the perspectives of our research and turning memory work into a pedagogical tool, we decided to experiment with a course at Tampere University, Finland. We designed the course specifically to Masters students and entitled it “Schooling and childhoods in socialist and post-socialist societies”. For us this title also signals the connections between the disciplinary fields of education, childhood studies, anthropology, history and politics that our project and course traverse.

By bringing memory work from our research to teaching, we aim to open spaces to explore subjectivity in the study of education practice and children’s everyday life in different societies. Memory helps “to incorporate embodied, familial, emotional, temporal, contextual, and cognitive interpretations of past and present, … to make our pasts useable for our futures.” (Clift and Clift, 2017, p. 605). Our course sought to inquire into childhoods and children’s everyday life and schooling in socialist and post-socialist societies from different thematic and disciplinary areas and by using memories of participants to connect with historical experiences and recent issues ailing our societies and education systems at large. The questions that oriented our course were:

- How was it like to be a child in former socialist countries?

- To what extent this childhood differed from childhoods under other political regimes?

- How can we deploy adults’ childhood memories to revisit lived childhood?

Our course was supported by external funding from the Expertise in Russian and Eastern European Studies (ExpREES) network and the New Social Research programme at Tampere University.

We framed the course within the scholarship of the politics of childhood and schooling, and their complex relationships. We examined the provision of kindergarten and school education, the everyday experiences of children in institutions of formal education, in the contexts of socialist and post-socialist societies of Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. We also looked at childhood beyond school settings, that is, as experienced in hobbies or free play. In addition to focusing on children, we discussed the roles of adults, such as teachers and parents, in these contexts.

We aimed to illuminate changing political regimes and societal transformations from the Cold War era to today and how these changes intersected in children’s lives. We highlighted the multiple connections that existed between the “East” and “West” spanning education policies and practices, the production of expert knowledge on childhood and education, and the lived experiences of schooling or unsupervised play.

Deploying scholarly research and personal experiences from memory stories, we sought to both introduce students to the theme of the course and to shake possible myths of a homogenous education space that supposedly unified the socialist world through a unidirectional delivery of ideologized education content and socialization, and disconnected it from the education systems and experiences on the other side of the Iron Curtain. Some of the students in our course came with personal knowledge of and connection to socialist regimes and ideologies, as they themselves grew up in these countries. Others did not share this background, but felt instantly connected to the topic, as our open discussions during lectures and reading seminars prompted continuous reflections on one’s own childhood, problematizing the image of a clear-cut division between ‘East’ and ‘West’.

Topical issues explored

Some lectures focused primarily on a particular aspect of education in the period of historical socialism. Others shed light on educational transformations after the fall of the Berlin Wall. They critically examined the supposed end of socialist education practices and questioned unidirectional educational transformations driven by Western experts and discourses.

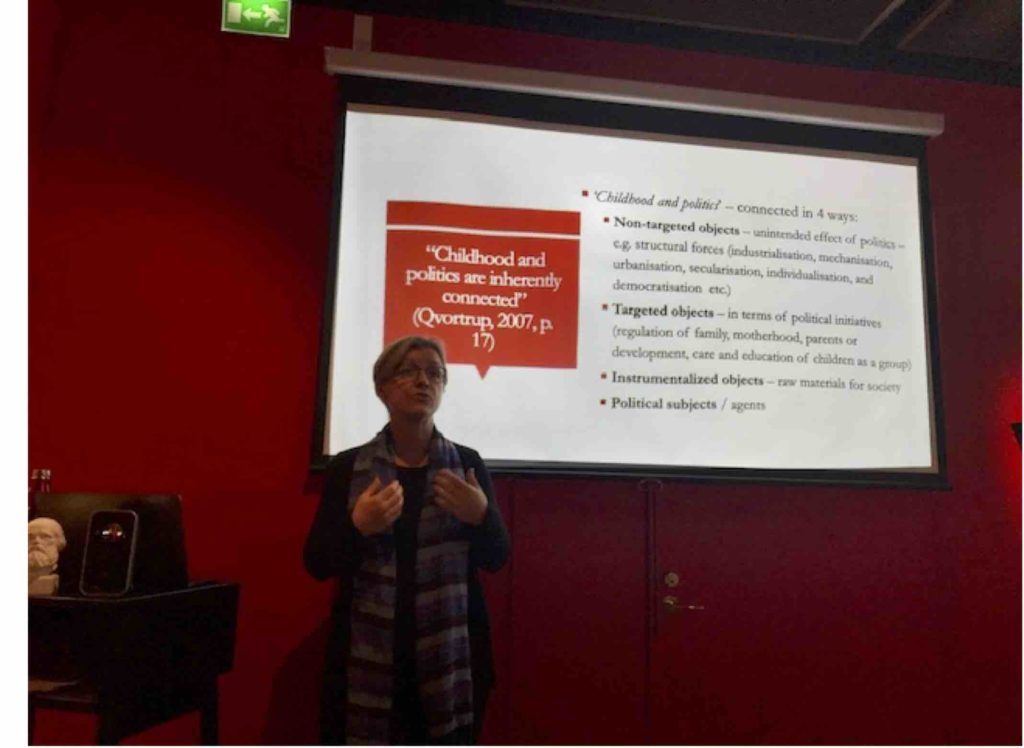

We invited a number of renowned guest speakers from Finland and abroad. In addition and thanks to our close ongoing collaboration with the Labour Museum Werstas, we organized the first session of the course in the Lenin museum, combining the introductory lecture with a museum visit. In the fitting environment of the museum, where a special sub-section explores the pioneer movement in a comparative manner within the Soviet Union and Finland, Professor Zsuzsa Millei introduced the theme of the course in her lecture titled “Socialism and childhood”.

She started by briefly revisiting the role and image of children under socialism as well as the conceptual literature on the diverse connections between children and politics. Socialism aimed to create new, morally and psychologically superior human beings, whose consciousness would be re-oriented away from materialism and individuality (capitalism). The focus on the development and socialization of children and the creation of ideal childhood were therefore vital. Symbolically, children became the icons of the present and future of socialist revolution, and resources for bringing about a more equal and community-oriented society. Children were seen as important civic and political actors and as an impressionable segment of the population and hence as embodying the possibility of a new social order. This importance of childhood facilitated the development of child related sciences and professional knowledge across the countries of the ssocialist bloc. This level of interest associated with childhood is paralleled in history but very specific in nature. Zsuzsa concluded by explaining how focus on childhood and children’s everyday experiences offers significant insights into children’s political life today and helps debunk knowledge produced about socialist childhood during the Cold War era.

Zooming in on the theme of politics in childhood and socialism,Professor Iveta Silova examined the manifestations of the Soviet nation-building project in relation to children’s everyday experiences in school and at home in her lecture “Lessons in nationhood: Political subject formation and agency in (post)soialist childhoods”. She demonstrated how the Soviet regime placed children at the center of complex and contradictory political socialization processes that aimed to simultaneously forge a common Soviet identity while promoting national languages and cultures. This ambitious nation-building project was explicitly taught in the official school curriculum and further reinforced through children’s participation in political youth organizations. In addition, children learned the Soviet nationhood through mundane, everyday practices.

Building on the work of John E. Fox and others, her talk examined the ordinary, taken-for-granted expressions of nationalism made visible by retelling childhood memories of ‘breaching’ the nation – that is, the instances when the unspoken order of the Soviet ‘nation’ was unexpectedly upset and needed to be restored – through such everyday experiences as wearing (or not) a hair-bow or sharing jokes about bows in girls’ hair.

Adding a new aspect to explorations of institutional childhoods, Dr. Ewa Sidorenko’s “Childhood in informal settings: Polish childhood under communism, memories of unsupervised play and children’s perceptions of the world” explored the complexities of childhoods in urban Poland in the last two decades of communism by focusing on formal institutional settings on the one hand, and children’s free play experiences on the other. Whilst the official public life including all educational and organized leisure institutions were under strict ideological control of the communist regime, many primary school aged children enjoyed hours of free time after their school, away from adult supervision during which they exercised their agency by playing, socializing, roaming, taking risks to a degree greater than the subsequent generations of children growing up in Poland after 1989.

Instead of exploring developmental outcomes of such complex structuring of childhoods under communism, Ewa’s lecture focused on the ideological and governmental techniques used by the state on children as communist citizens in the making. Then she explored some of the children’s experiences with unsupervised free play. The themes used to examine such experiences were risk taking, increasing awareness and making sense of social inequalities, navigating the public and the private and visibility of and engagement with Western material cultures. Finally, Ewa considered methodologies suitable for exploring lives under communism.

Dr. Jennifer Patico’s online lecture “Childhood and transformation of educational institutions – Russian teachers’ perspective” drew on her ethnographic fieldwork in St. Petersburg, Russia, in the early 1990s. In that project, she explored how schoolteachers in the city navigated a changing economic and moral landscape in the early years of postsocialism. For example, teachers tended to be wary of the “New Russians” who were suddenly accumulating wealth through commerce and who were the butt of many popular jokes. At school, teachers also came face to face with this new wealth – through the parents of their students – and with challenges to their own institutional and moral authority as teachers. The lecture examined how post-Soviet teachers’ values and expectations surrounding “culturedness,” education and social status linked their professional lives with their broader senses of class and consumer identity. Jennifer explored post-socialist transformations in an insightful way. She discussed how these changes manifested in the everyday life and changing norms and values of teachers, who themselves underwent an intensive self-questioning of the meaning of education, the role of teachers and families in their children’s education and school choice, and teachers’ role in building of a society through children’s education but after communism a very different type to what existed before.

Dr. Meri Kulmala’s lecture “Childhood and institutional care in and after socialism” was unfortunately interrupted by the abrupt measures introduced to prevent the spread of COVID-19, and was therefore presented through written materials that the students studied independently. Meri’s work expands on Jennifer’s lecture by examining Russian child welfare reforms through a rich set of data containing statistics and qualitative interviews with child protection officials, practitioners and experts. Her lecture materials focused on the reform from the old Soviet-type system, dominated by residential care in large institutions, to preventive support services (birth families) and alternative care in families (foster families) or in family-like environments (small units).

These reforms are embedded in a fundamental change in understanding the child’s best interest and best possible care. In examining the background and implementation of the reform, Meri also revisited the Soviet-era care for children, showing how the Soviet model of child protection was based on the paternalist idea of the state as the primary caregiver and prioritized residential care by state professionals. Finally, Meri compared child welfare reforms in Russia to those in other post-Soviet countries, such as Kazakhstan, highlighting that despite similar institutional legacies and post-Soviet conditions, the deinstitutionalization of child welfare reforms have produced differing outcomes.

The course concluded with an online conference in which students presented their essays engaging with a theme picked from the lectures. To explore these themes, they drew on scholarly literature and personal experiences told as childhood memories. The topics ranged from one’s own socialist identity framed by the ambiguities of the socialist regime that failed to foster a uniform value system amongst its subjects, to banal nationalism in children’s experiences of schooling and free time. Students examined the discourses of nationalism and their manifestations in familiar material culture, such as books, music or clothes, including school uniforms. One presentation inquired into the often ignored space of schools, namely, school toilets, that enabled surprising experiences of privacy, solidarity, dissent and social class.

We think it is justified to name this series of presentations as a mini-conference, since students became part of our research community during this course. They offered their views, added to and critiqued our approach and conceptualisations of childhood in socialist societies. Memory work in their presentations has been used as a constructive tool and extended the learning spaces and possibilities of personal engagements also in this course. We hope their interest in memory work and our project will continue.