by Simona Szakács-Behling

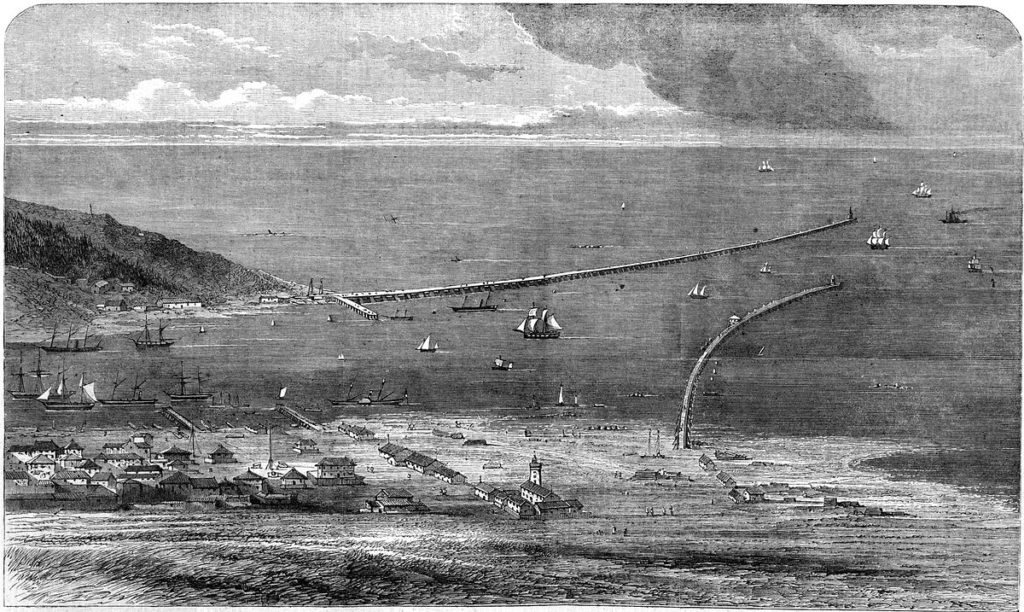

The story I’m about to tell is a story in three acts based on my memories of travelling with my grandfather from Bucharest to his native village of CA Rossetti in the Danube Delta during several summers in the early 1990s. I must have been between eight and eleven years old, at a time when I thought that adults are not afraid of anything and they never feel pain – not even when they go to the dentist or get an injection. My memories interweave snippets of different trips that took place on the same route (Bucharest to Tulcea by train, Tulcea to Sulina by ship, Sulina to Cardon by boat, Cardon to CA Rossetti by tractor), featuring the same two protagonists, snippets that I cannot disentangle from each other. It is, thus, a story ‘braided’ from different singular moments in time – threads that I cannot neatly assign to specific trips. Instead, they stand braided together, as a ‘single’ thread of memory of my summer journeys to the Delta.

But this story is about more than multiple journeys to a certain geographic place, crossing urban/rural boundaries. It is more than the story of moving through space from a country’s capital to one of its border regions – the Dobrudja (Dobrogea) – the easternmost point of Romania, where the Danube meets the Black Sea. It is also a story of growing up, a story about multiple transgressions, a story about the crossing of various boundaries. A story about the unknown, about excitement, fear, trust and authority. A story about intergenerational conversations and contestations, about enactments and re-enactments, about learning and rehearsing how to be an adult, about negotiation and following examples, about legitimizing stories, breaking rules and creating habits. A story about nostalgia, returning to one’s roots and traveling in time, a story of initiation into family history and of (re)creating family tradition. It is a story about world-making through movement. A story about becoming and about being, together, in time as much as in space.

The stories interweaved here took place between 1991-1993, in a time period of profound post-socialist transformation and economic change for Romania. Dobrudja, historically a multicultural border region subjected to intense Romanianisation and assimilation policies during nation-building at the turn of the 20th century (Iordachi 2002) but also a region that is undercut by multiple power/knowledge marginalisation policies at the turn of the 21st (Van Assche et al 2011), was undergoing severe socio-economic scarcity in the early 1990s when these trips were taken. My grandfather, who was born in 1905 and lived until 1997, had ran away as a young boy from his village in the Delta where his parents were farmers, to Bucharest, the city where one of his uncles lived, to fulfil his dream of pursuing education beyond elementary level. His was an idealized vision of the village he had left behind as a young boy, a village “on a bank of sand”, so fertile that everything would grow just like in the Garden of Eden – as he used to say.

Our last visit to the Delta together was heart-breaking for my grandfather. Unlike all other times, we had to break off our trip. From Sulina (the last city before the Danube flows into the sea), we returned to Bucharest and left our usual journey deep into the Delta unfinished. The so-called ‘transition’ to a market economy in the early 1990s had brought with it high levels of unemployment, severe changes to the natural landscape and unimaginable disillusionment among the local population (see Teampău & Van Assche 2015). “There is no more fish”– our relatives told us, the worst nightmare for a people whose livelihoods depended on fishery. There was a cockroach invasion on the streets of Sulina, the port and shipyard were rusting in disrepair, water distribution was heavily interrupted, leaving residents with one hour of water a day. Incomprehensible as it was to me as a child, my grandfather explained to me that we could not travel to the village anymore. He could not bear to see his beloved Delta fallen in degradation like this, the happy place of his childhood becoming a ghost-town. The story I tell here is the story of our journeys as he would have probably liked to remember them: a story of joyful conviviality, excitement, adventure, and learning to pursue dreams, even when they are not your own – but interwoven with a little girls’ encounters with becoming a ‘fearless’ adult, breaking, making, and being afraid of her own rules.

ACT 1: The Flying Curtain

We leave our apartment in central Bucharest very early in the morning. We have a long day ahead of us: we shall arrive at cousin Petrică’s home in the village only as the sun goes down. We rush out to get on the tram to the station. We made it on time! We are in the train and get ourselves set for the long ride. The seats are made of some kind of brown, synthetic leather. They are smelly, stained, and disintegrate into threads at the corners. The sun is rising up as the train leaves Bucharest station. In the compartments everybody makes small talk. Where are you going, where are you from, what do you for a living, where do you live? My grandfather tells jokes and prompts me to make note of every railway station where the train stops. It will come in handy to document our trip for the Compunere (short essay for school) that I’ll have to write when we’re back. Like every year, the first task at school will be to write an essay about “how I spent my summer holiday”. Instead of listening to him and taking notes, I’m glued to the window, looking outside in wonder of the changing landscapes rushing past. There’s a lot of dust and a lot of fields that I usually only see among the pages of my textbooks. They are so different from the view from my window at home, on the ninth floor of an apartment building, overlooking a large boulevard with cars, buses, trams, and other nine-storied buildings. I am amazed that the train window is only exciting for my co-passengers because of its open/closed status. They discuss vigorously whether, when, and how long it should be left open – because of the ‘current’ of air that it summons in and could get everyone sick. The agreement is to open it only in the stations so that everyone gets a chance to get a breath of fresh air by sticking their head out, some even smoking a cigarette. When the train stops and the window is opened, I am allowed to stand up, my feet on the seat (unimaginable otherwise), to get my head out and look outside. When the train starts moving again, the brown curtain flutters out as if trying to fly away before the window will be closed. The sun shines through the dark-rimmed cigarette holes in the curtain’s brown fabric, embossed with the word “CFR” (which stands for the name of the railway company, Calea Ferată Română). I wonder what it would be like if the curtain just took off, like a balloon. Where would it go? How would it dance in the wind?

ACT 2: The Captain’s View

After about four hours, we arrive in Tulcea. The port is right across the railways. We are waiting about half an hour or so to get on a large ship that goes to Sulina. The ship is large and I feel small. The ship has a few decks and makes loud noises. We find some seats and put our luggage down, before we get out on the deck. The air smells so different here and there’s the sharp wind, stinging my cheeks. My grandfather says that there will be a split in the Danube. It would be great if I could be upstairs on the upper deck to see this moment when the ship takes a turn on one of the canals. He tells me to go up to the captain and ask to be allowed to see the Danube from up there. My aunt – whom I have never met because she fled to America in the 1970s – did this too when she was a little girl, he tells me. I was named after her and I am born in the same zodiac sign – the Leo. If my aunt Simona could do it, why couldn’t I? I shouldn’t be afraid to go up to him. But I am. I am terrified. I see signs saying it is prohibited for passengers to go up there. What if the captain gets upset because I’m not allowed to go up there? My heart is beating fast with anxiety but I do not want to disappoint my grandfather. I cannot be any less than my aunt. What would I write in the Compunere if I don’t dare to go up? How can I describe the beauty of the Danube if I do not see it myself from the upper deck? My grandfather insists. You won’t get very far in life if you don’t have guts, he says. You have to do what you have to do. And be proud about. Finally, I go up, but on condition that he comes with me. I go shyly, feeling ashamed. My cheeks must be very red. But I trust my grandfather. He surely knows what he’s doing, he’s done it before. If my Simona aunt did it too, and it worked, it must work now too. Excuse me, Mr. Captain, may I see the Danube from up here? I have to write an essay about the beauty of the Danube for school – my legs are shaking, my voice is trembling. The captain sees me, looks at the old man in his grey suit right behind me, smiles and allows me on his seat without any resistance. I am watching the Danube from the captain’s view. I have no idea how it feels or how to describe it. I know it’s supposed to be beautiful, so I guess it is. What a brave little girl. Your teacher will be so happy to read your Compunere and your colleagues will wish they had your courage to go up to the Captain! Everyone is happy, and I am relieved. And that’s the most beautiful feeling of all.

ACT 3: Riders of the Storm

We arrive in Sulina where we wait for another boat, a smaller one. It’s a Şalupă that is long and has only one deck. We get on a narrow canal of the river Danube towards the village Cardon. All I see is luxuriant vegetation on both sides, caressed by the wind, and birds. Many birds. When we arrive in Cardon, it starts getting dark. Not because the sun is setting but because a storm is coming. Grey heavy clouds are hanging down. The only means of transportation from Cardon onwards is a tractor that will take us ‘in-land’. I am amazed how empty the space is. It’s just sand and dust. I see no houses, no people, and I’m starting to feel cold. A thunderstorm is upon us. The tractor has a trailer where everyone is packed. We get a prelată (a thick plastic cover) to cover ourselves with in case it starts raining. The first thunder strikes and we’re in the middle of nowhere, in an open, empty field, riding on the back of a tractor. It’s scary and cold. The thunders keep striking. Will we get there soon, grandpa? My grandfather is in a good mood, he doesn’t seem to be afraid of anything. He again makes small talk with our co-passengers. He’s laughing and he’s happy. Nobody else seems to be scared of the looming storm. The tractor ride is bumpy, there’s no road. I feel as if we’re making our own road through the dusty earth. Big drops of rain start falling and they make a noise on the prelată that everybody is holding up now, arms stretched over our heads. I feel like in a womb.

We arrive in CA Rossetti, the village where my grandfather was born. Now, we only have to find my cousin’s home, he announces cheerfully. But will pass by the post-office first, to say hi to my friend who works there. We get our luggage down, and start walking through the dusty-muddy road. Luckily, the storm only lasted a few minutes.

References

Iordachi, C. (2002). Citizenship, Nation-and State-Building: The Integration of Northern Dobrogea into Romania, 1878-1913. The Carl Beck Papers in Russian and East European Studies, (1607), 86. https://doi.org/10.5195/CBP.2002.93

Teampău P. and K. Van Assche. (2015). Pirates, Fish and Tourists: The Life of Post-Communist Sulina. Pp. 185-196 in Iordachi C. & K.Van Assche (eds.) The Biopolitics of the Danube Delta: Nature, History, Policies. Lanham: Lexington Books

Van Assche, K., Duineveld, M., Beunen, R., & Teampău, P. (2011). Delineating Locals: Transformations of Knowledge/Power and the Governance of the Danube Delta. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 13(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2011.559087

Simona is a post-doctoral researcher at the Georg-Eckert-Institute – Leibniz Institute for International Textbook Research in Braunschweig (Germany) where she has worked since completing her PhD in Sociology at the University of Essex (UK). Her research is concerned with Europeanization, global cultural change, and post-socialist transformations in education from a transnational, qualitative, and comparative perspective. In her current work she focuses on solidarity and global citizenship education across different school forms that are embedded in inter-/trans-nationalizing structures. She is passionate about photography, border crossings and mountains.